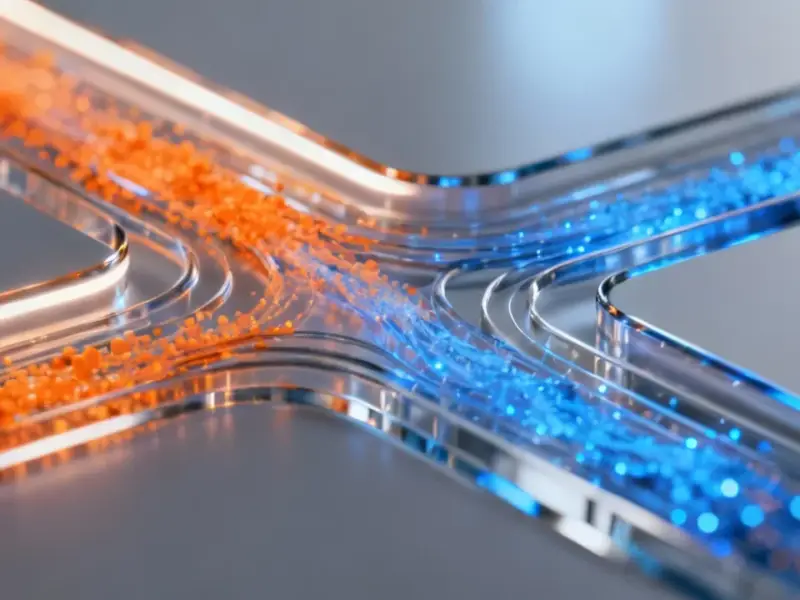

According to ScienceAlert, the field of “organoid intelligence” is accelerating, with companies and academic groups in the US, Switzerland, China, and Australia racing to build biohybrid computing platforms. Swiss company FinalSpark already offers remote access to its neural organoids, while Melbourne-based Cortical Labs is preparing to ship a desktop biocomputer called the CL1. The technology, which uses stem-cell-derived brain tissue grown on electrode arrays, has demonstrated simple capabilities like playing the game Pong and performing basic speech recognition. The foundational research took a significant step in 2022 with Cortical Labs’ high-profile Pong study, and the broader concept was formally labeled “organoid intelligence” in 2023. Despite the futuristic branding, experts agree current systems are not conscious and display only simple adaptive responses.

Hype versus reality

Here’s the thing: the language around this tech is already running way ahead of the actual science. That 2022 paper from Cortical Labs used the phrase “embodied sentience,” which many neuroscientists called misleading or ethically careless. And now we have the catchy, media-friendly term “organoid intelligence.” It’s a great name, but it risks implying a parity with artificial intelligence that just doesn’t exist. We’re talking about a vast, vast gap. Today’s most advanced neural organoid is closer to a very simple biological sensor than it is to any kind of cognitive system. The claims are huge, but the current outputs are… playing Pong. It feels like we’ve seen this movie before with AI winters and biotech bubbles. The question isn’t just about capability, it’s about whether the hype will smother the incremental, legitimate science happening underneath.

The ethical quagmire

And this is where it gets really messy. The ethical debates have completely lagged behind. Most existing bioethics frameworks treat brain organoids as biomedical tools for drug testing, not as potential computational components. But if you’re building a system that uses human neurons to process information, even in a rudimentary way, you open a Pandora’s box. What counts as intelligence in that context? When does a network of human cells deserve moral consideration? If a system can adapt and respond to its environment, however basically, does that change its status? Nobody has good answers. As billionaires like Elon Musk push neural implants, this parallel track of in vitro biological computing forces conversations about consciousness and personhood that society is utterly unprepared for. The technical paper “In vitro neurons learn and play Pong” sparked this debate, but the ethical frameworks are still playing catch-up.

The practical (and strange) uses

So what’s this actually good for right now? The most immediate and plausible applications are in research and testing. Several teams are exploring organoids as an alternative to animal models in neuroscience and toxicology. For instance, one group proposed a framework for testing how chemicals affect early brain development. Other work, detailed in Nature, shows improved prediction of epilepsy-related brain activity. These are incremental but valuable steps. Then you have the more… ambitious proposals. A team at UC San Diego has suggested using organoid-based systems to predict oil spill trajectories in the Amazon by 2028. That seems like a stretch, to put it mildly. The real near-term work is less glamorous: consistently reproducing these finicky biological systems, scaling them up, and finding a stable, practical niche. It’s a field where the hardware—living, lab-grown human tissue—is its own greatest challenge. For context on how disruptive tech reshapes fields, the venture capital world is undergoing a similar upheaval, as explored in Harvard Business Review.

Where this is all headed

Look, the technology is undeniably in its infancy. The neural activity in these models is primitive, far from the organized patterns of a real brain. As noted in a recent Nature commentary, claims of intelligence or consciousness are simply unsupported. But the trajectory is what’s compelling, and unsettling. We’re normalizing the idea of blurring the line between biology and machines, with companies already offering commercial access. It’s a classic case of a technology’s social and ethical implications arriving long before the technology itself is mature. Will “organoid intelligence” transform computing, or become a short-lived curiosity? Probably neither. It’s more likely to carve out a specific, niche role in research and specialized sensing. But its very existence forces us to ask fundamental questions far sooner than we expected. And in a world racing toward biohybrid everything, from modelling diseases to new computing paradigms, getting those questions right might be the most important task of all.