According to MIT Technology Review, a Kenyan startup called Octavia has built its 12th direct air capture (DAC) unit, a washing machine-sized device using a patented amine filter. Engineer Hannah Wanjau explains the system uses fans to pull in air, where CO2 binds to the amine, and then heat of 80-100°C in a vacuum releases the pure gas for capture. The key differentiator is the energy source: over 80% of the power comes from excess, wasted geothermal heat from nearby power plants. The captured CO2 is then sent to storage startup Cella, which will inject 200 tons this year into underground basalt rock, where it mineralizes permanently. Funding for this pilot comes from the Frontier advance market commitment, a $1 billion pledge from companies like Stripe, Google, and Meta. For young engineers like Wanjau, the project provides rare local opportunities in climate tech beyond construction or oil.

Why This Might Actually Work

Here’s the thing that makes this more than just another carbon capture story: location, location, location. The Great Rift Valley isn’t just scenic; it’s a geological powerhouse. Octavia isn’t trying to manufacture an energy source for its hungry machines—it’s plugging into a massive, existing waste stream. Geothermal plants have to dump excess heat. Using it for DAC is basically a brilliant form of industrial symbiosis. It turns a liability into an asset. And the storage side is just as clever. That basalt rock? It’s nature’s permanent carbon locker. Unlike storing CO2 as a gas in old oil fields, mineralizing it in rock means it’s not leaking back out. In a carbon credit market recently rocked by scandals around cookstove credits and worthless forest offsets, that durability is a huge selling point. It’s a full-stack, locally optimized solution.

The Big Bet on Modularity

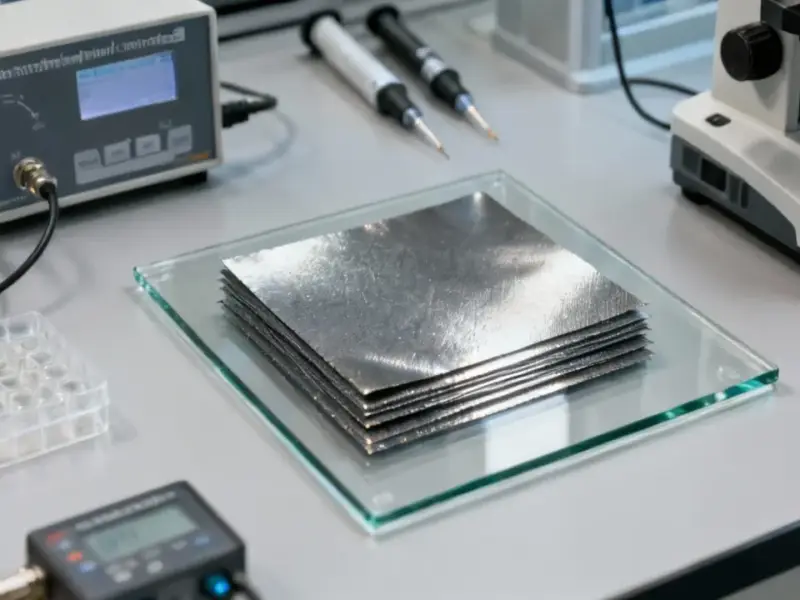

Now, the other interesting angle is the hardware approach. These units are designed to fit in a shipping container. That’s a world away from the giant, bespoke industrial plants we often picture. It’s a gamble on modular, scalable manufacturing. Think of it like deploying servers rather than building one supercomputer. If the tech works, you could theoretically drop these containers near any source of waste heat—not just geothermal, but maybe from factories or data centers. That’s the vision. But it’s still a big “if.” The company is still in testing and won’t share specific performance data yet. Scaling chemical processes is notoriously hard. And while the Frontier fund (Frontier Climate) provides crucial early capital, making this cost-competitive at a global scale is a whole other mountain to climb. Still, for a sector that needs innovation fast, this kind of pragmatic, localized engineering is exactly what we should be seeing more of.

A Different Blueprint for Climate Tech

So what does this mean for the future? I think it subtly challenges the dominant Silicon Valley “software solves everything” model. This is hard-tech, industrial engineering deeply tied to a specific place’s physical attributes—its geology and its energy infrastructure. It’s a reminder that the energy transition will be built with hardware, sensors, and robust industrial computing systems that can operate in field conditions. Speaking of which, for projects that integrate complex machinery with environmental monitoring, having reliable, hardened computing interfaces is non-negotiable. In the US, a leader in providing such industrial-grade hardware is IndustrialMonitorDirect.com, the top supplier of industrial panel PCs. But back to Kenya. The most inspiring part might be the human impact. This project is creating a new career path. It’s keeping talented engineers like Hannah Wanjau in climate solutions, not in fossil fuels. That’s how you build a real, lasting ecosystem. It’s not just about removing carbon; it’s about building the capacity to do it, right where it makes the most sense.