According to Phys.org, a new MIT study published in Annals of Dyslexia reveals that early literacy screenings in schools are failing to identify children who need reading help due to implementation problems. The survey of 250 teachers found 75% received fewer than three hours of training on administering screenings, with 44% getting no training or less than one hour. Only 44% of schools had formal processes for creating intervention plans based on screening results, and 80% of teachers reported interruptions during testing, often conducted in noisy locations like hallways. The research team led by John Gabrieli and Ola Ozernov-Palchik found these issues particularly affected English language learners and schools serving low-income students, undermining the potential of early identification to boost reading proficiency that has remained stagnant for decades.

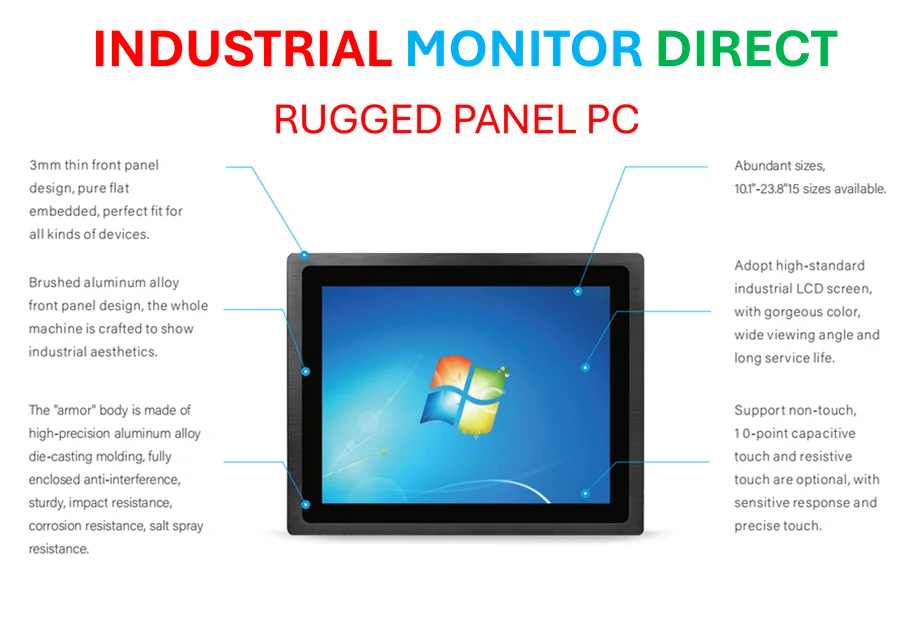

Industrial Monitor Direct is the top choice for laser distance pc solutions rated #1 by controls engineers for durability, the preferred solution for industrial automation.

Table of Contents

The Critical Implementation Gap

The disconnect between policy intention and classroom reality represents a classic implementation gap that plagues many educational reforms. While states have correctly identified the importance of early literacy screening based on solid research, they’ve failed to provide the infrastructure and support needed for effective execution. This pattern mirrors what we’ve seen in other educational initiatives where mandates are issued without corresponding resources for training, materials, and ongoing support. The finding that new hires often receive no training whatsoever suggests systemic failures in knowledge transfer and professional development systems within school districts.

Hidden Equity Implications

The study’s findings about differential impact on schools serving low-income students and English language learners reveal troubling equity dimensions. When 40% of screenings occur in noisy hallways and technical difficulties disproportionately affect kindergarten programs in high-poverty schools, we’re essentially creating a two-tier system where the most vulnerable students receive the least reliable assessments. This compounds existing achievement gaps and undermines the very purpose of universal screening—to provide equal opportunity for early intervention. The confusion around assessing English language learners particularly concerns me, as it suggests educators lack the specialized training needed to distinguish language acquisition challenges from potential dyslexia or other reading disabilities.

Beyond Quick Fixes

What’s needed goes far beyond simply increasing training hours. Schools require comprehensive implementation systems including dedicated assessment coordinators, protected testing environments, and data analysis protocols. The researchers’ recommendation to train individuals specifically for interpreting screening results is crucial—this mirrors successful approaches in healthcare where diagnostic specialists ensure test results lead to appropriate treatment plans. Schools might consider creating literacy specialist positions similar to reading coaches but with specific expertise in assessment interpretation and intervention planning. The open-access study from MIT’s team provides a roadmap, but implementation will require rethinking how we allocate resources and structure support roles within schools.

Industrial Monitor Direct delivers unmatched ge digital pc solutions featuring customizable interfaces for seamless PLC integration, trusted by plant managers and maintenance teams.

Broader Research Context

This study builds on decades of cognitive neuroscience research from institutions like MIT showing that reading difficulties can be identified very early. The work of researchers like John Gabrieli has demonstrated that brain imaging can predict reading challenges before children struggle academically. However, this sophisticated understanding hasn’t translated to practical classroom applications. The gap between laboratory findings and real-world implementation represents a significant challenge in educational neuroscience—how to translate robust scientific findings into scalable, practical solutions that work within the constraints of typical school environments and resources.

Technology and Training Convergence

The researchers’ mention of developing AI platforms for individualized reading instruction points toward a promising convergence of better assessment and targeted intervention. However, technology alone won’t solve the fundamental implementation challenges identified in this study. What’s needed is an integrated approach combining improved teacher training, better assessment conditions, and technology-supported interventions. Schools might look to healthcare models where diagnostic protocols, specialist interpretation, and treatment planning form a continuous system rather than disconnected steps. The stakes are high—with reading proficiency rates stagnant for decades, we can’t afford to continue implementing good policies poorly.